DECOLONIZING LANGUAGE AS A PRACTICE OF PEACE: BOTANICAL NAMING AND EPISTEMIC VIOLENCE IN THE CARIBBEAN AND LATIN AMERICA

Ongoing research project as the first artist in residence at the National Botanical Garden of the Dominican Republic

Upcoming Presentations, Lectures, and Publications:

-World House Project Conference for Peace, University of Yucatán, Mérida, Mexico (2026)

- International José Martí Colloquium for a Culture of Nature, Havana, Cuba (2026)

- Botanical Bridges Congress, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (2026)

-Workshop and Public Lectures, Columbia University, New York, USA (2027)

As an artist in residence at the National Botanical Garden of the Dominican Republic, I’m exploring how colonial, racial, and gendered violence is encoded in the naming of plants across Latin America and the Caribbean. Our botanical dictionaries list popular names like Mala Madre (bad mother), Mala Mujer (bad woman), Bruja (witch), Tullida (crippled woman), Mota de Negro (Black fuzz), Cabeza de Indio (Indian’s head), and Bandera Española (Spanish flag), revealing how language inscribed hierarchies of race, gender, and ability onto the natural world.

To begin, I’m focusing on case studies from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, and Mexico. Naming has shaped both social imagination and environmental relationships, influencing how communities value, protect, or harm their surroundings.

As public school students remain the largest audiences for these gardens, my research explores how art-based interventions can foster environmental awareness, dignity, and collective healing. Decolonizing language becomes a pathway toward ecological justice, historical repair, and sustainable, peaceful futures.

Working With Botanical Gardens:

Presenting this ongoing research to the directors and team members of the National Botanical Garden of the Dominican Republic meant opening a new conversation within an institution historically framed by scientific authority. From an artist’s perspective, there is little precedent for this kind of inquiry — one that questions the colonial and patriarchal structures embedded in botanical nomenclature itself. For decades, these names have been accepted “in the name of science,” without examining the epistemic violence they carry. This project invites the institution to look inward, to recognize that language — even scientific language — is never neutral, and that transforming it is also a practice of care and collective responsibility.

Popular names are not just names. Once inscribed into official systems of classification, they cease to be colloquial and become part of the academic record — formal, institutional, legitimized. This is how linguistic violence turns into material violence: words shape perception, and perception shapes the world. Within the botanical gardens, official signs replicate that violence without question. Every day, thousands of students from public schools, and visitors in general, read these names — learning, perhaps unconsciously, to naturalize a hierarchy that language first created.

Presenting this ongoing research to the directors and team members of the National Botanical Garden of the Dominican Republic meant opening a new conversation within an institution historically framed by scientific authority. From an artist’s perspective, there is little precedent for this kind of inquiry — one that questions the colonial and patriarchal structures embedded in botanical nomenclature itself. For decades, these names have been accepted “in the name of science,” without examining the epistemic violence they carry. This project invites the institution to look inward, to recognize that language — even scientific language — is never neutral, and that transforming it is also a practice of care and collective responsibility.

Studying each plant and tracing the reasons behind its popular name, in collaboration with the team of the National Herbarium, becomes a way of revealing how language preserves systems of value, desire, and exclusion. These names — often dismissed as merely “popular” or “vernacular” — carry within them the traces of a collective imagination shaped by colonial history, gendered perception, and local cosmologies.

Collaborating with the team of the National Herbarium

Plant "Mala Mujer" (Bad Woman)

Plant "Mala Mujer" (Bad Woman) under the microscope

Plant "Mala Mujer" (Bad Woman) under the microscope.

Plant "Mala Madre (Bad Mother) | Popular names are never just names. Once inscribed into official systems of classification, they cease to be colloquial and become part of the academic record — formal, institutional, legitimized. This is how linguistic violence turns into material violence: words shape perception, and perception shapes the world.

Here, within the Botanical Garden, an official sign replicates that violence without question. Every day, thousands of students from public schools, women, mothers, and visitors read these names — learning, perhaps unconsciously, to naturalize a hierarchy that language first created.

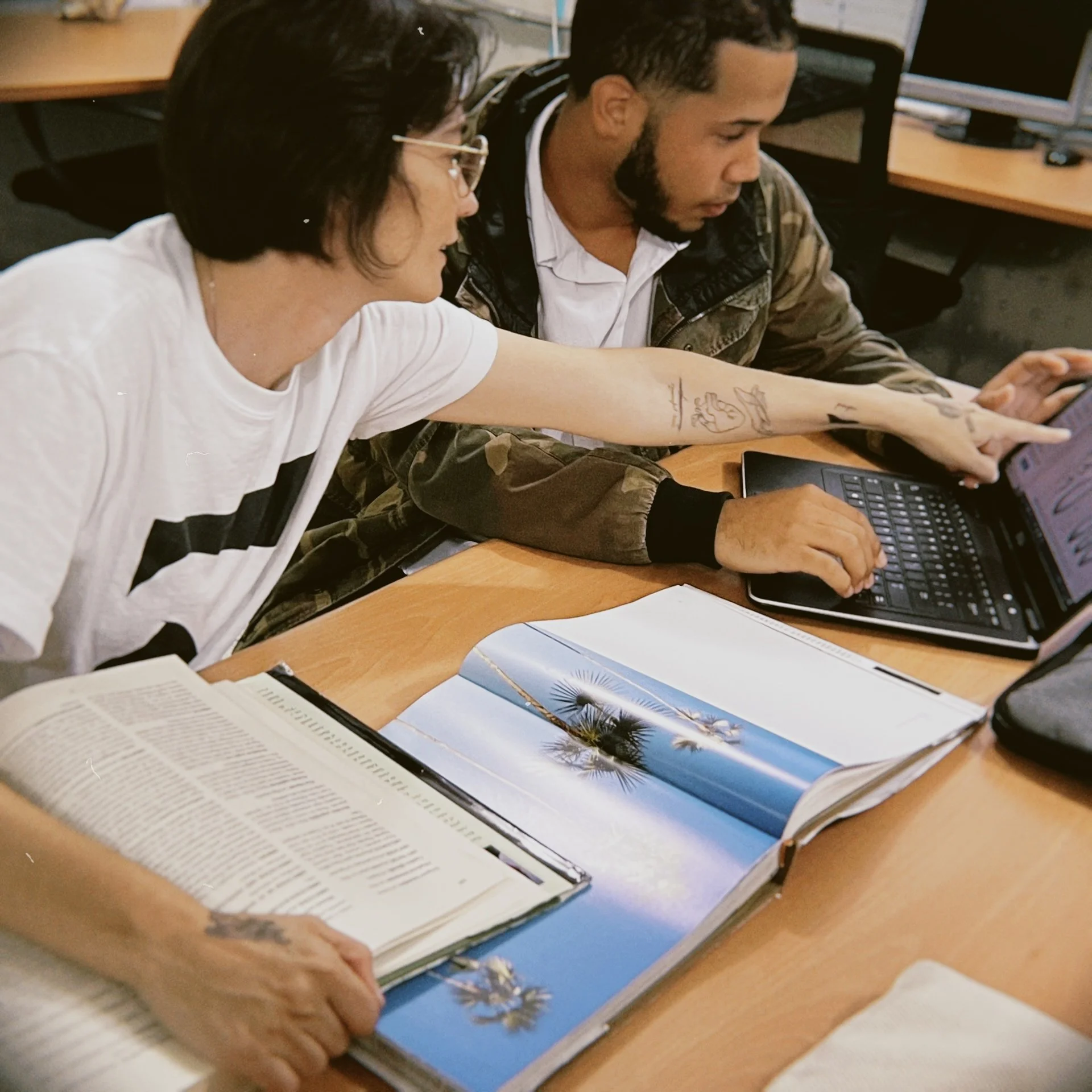

Workshops with public school students invite collective reflection and critical thinking.

Together, we ask: Who names the world? How would a plant name itself? What happens when a plant is called “bad mother”? These questions open a space to think about language as a living structure — one that shapes how we relate to what surrounds us.

Through these encounters, naming becomes an act of consciousness: an opportunity to unlearn inherited hierarchies and imagine other, more caring ways of describing the world.